A Success Story

Food fortification is a public health success story.

Iodized salt is just one example. In 1990 world leaders gathered at the UN and launched a global movement for universal salt iodization to protect the developing brains of children. With the effective collaboration of national governments, international and civil society organizations and the salt industry, the proportion of households consuming iodized salt worldwide increased from less than 20% in the early 1990s to almost 90% today, and the number of countries with iodine deficiency (the world’s leading cause of preventable mental impairment) decreased from 113 in 1993 to just 21 in 2021.1

Food fortification is not new. Most of the world’s wealthy nations have supported the health of their own populations by using fortification for almost 100 years.

In Canada, food fortification is something we simply take for granted: iodine in our salt, Vitamin D in our milk, B vitamins, folic acid, and iron in our all-purpose flour. Fortification has led to the successful elimination of many preventable diet-related diseases in Canada. Fortification began in Canada in the early 1900s to address diseases resulting from nutrient deficiencies. In the 1940s, beriberi and blindness in segments of the population in Newfoundland led to the mandatory addition of B vitamins, calcium, and iron to flour, and vitamin A to margarine. The national iodization of salt in 1949 eliminated goiter in Canada, and the addition of vitamin D to a broadening range of milk products in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s eliminated rickets as a widespread public health issue.2 We continue to rely on food fortification to prevent disease and support the health of Canadians.

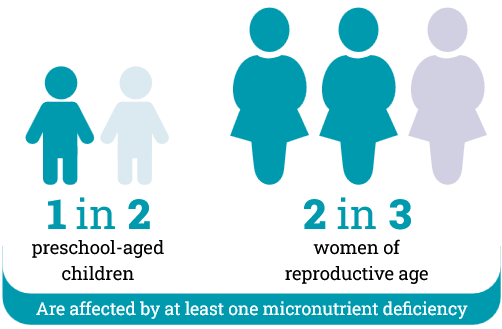

Globally...

Proven, Cost-Effective, Equitable

According to the World Food Program, food fortification is one of the most sustainable, scientifically proven, and cost-effective ways to prevent micronutrient deficiencies on a large scale.3 The evidence is long-established. Fortifying salt with iodine helps to prevent irreversible brain damage in young children. Fortifying flour with iron helps to protect against anemia, and fortifying flour with folic acid helps to reduce the occurence of neural tube birth defects. Fortifying staple foods with vitamin A supports eyesight, boosts immune systems, and can save hundreds of thousands of lives each year.4 People in all countries, not just wealthy ones, should have access to quality, fortified foods.

Fortification of commonly eaten foods, such as wheat and maize flours, rice, pulses, cooking oil, and salt, costs just pennies per person per year and can easily reach billions of people through their regular diets. By targeting the staple foods eaten by everyone – young and old, rich and poor, rural and urban -- fortification ensures that even the poorest families have a baseline of vitamin and mineral security built into their diets. This is vitally important for pregnant and breastfeeding women and their children. Food fortification can help boost nutrient intake during that critical 1000-day window of rapid child growth and development and beyond. Food fortification is not meant as a replacement for a healthy, diverse diet, but serves as a complement to other nutrition and health initiatives. It is a crucial intervention that prevents disease and helps to ensure that food systems deliver a more nutritious diet for all.

Many countries currently mandate some form of food fortification, but implementation varies widely. According to a recent study, 84 low- and middle-income countries could benefit from establishing new mandatory fortification programs, and most existing programs could be strengthened to reach more people with more nutritious food.5 The Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) argues that large-scale food fortification is currently a massively underutilized tool in the world’s efforts to end preventable diseases and deaths.6 In 2023, over 50 civil society organizations signed a joint letter calling on the World Health Organization to "accelerate efforts for preventing micronutrient deficiencies and their consequences, including spina bifida and other neural tube defects, through safe and effective food fortification". A resolution to this effect, put forward by Canada, the European Union, and eight other countries, was unanimously adopted at the 76th World Health Assembly in May 2023. Much work is still to be done.

Biofortification

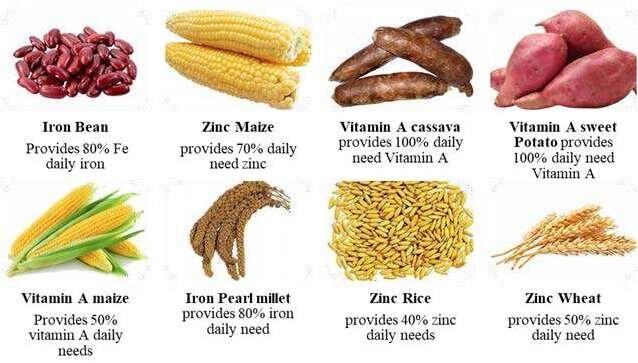

While food fortification occurs post-harvest, during processing, there is also the possibility of fortifying the crops themselves. This is called biofortification. Biofortified crops have been developed specifically for rural food systems in the Global South, where deficiencies in vitamin A, iron, and zinc are highly prevalent. Smallholder farming families eat mostly what they grow themselves, and often cannot afford nutritionally diverse diets. These rural families are not always easily reached by commercial food fortification or supplementation initiatives.

In partnership with smallholder farmers, crop scientists have developed strains of wheat, rice, and maize that are high in zinc, cassava, maize, and sweet potatoes high in Vitamin A, and beans, lentils and millet high in iron. These are varieties of familiar staple crops that smallholder families already know, grow, eat, and sell. These biofortified food crops are improving the nutrition, health, and livelihoods of increasing numbers of smallholder farming families in the Global South. Over the past 20 years, the pioneering biofortification organization, HarvestPlus, has been scaling up biofortification as a nutrition response and livelihood benefit for rural and low-income communities. To date they have released more than 400 varieties of biofortified crops in 41 countries. HarvestPlus has set an ambitious goal of 1 billion people regularly eating nutritious biofortified crops and foods by 2030.7

Dig Deeper…

- What is Food Fortification? Watch this 3-minute video from the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) for a quick primer.

- New Global Estimates for Hidden Hunger – Read this 3-page brief on micronutrient deficiency levels worldwide to get an overview of the breadth of the problem.

- Rice: A Photo Essay -- Follow the path of rice fortification and distribution in Bangladesh in this informative photo essay from Canadian NGO Nutrition International.

- Biofortification: It All Starts with a Seed – This animated 3-minute video gives a brief overview of the process of biofortification and the work of HarvestPlus.

- Biofortification and Women's Nutrition -- Read this 2-page info sheet to learn how biofortified crops are addressing rural women's nutritional needs.

- Orange Fleshed Sweet Potatoes -- Watch this 4-minute video about the introduction of orange-fleshed sweet potatoes high in vitamin A to communities in Tanzania.

- For those interested in which foods in Canada must be fortified, along with which foods may be voluntarily fortified, click here.

[This is the fifth installment of GRAN Small Sips focused on child hunger.]